Why Most Runners Shouldn’t Worry About Cadence

While we've heard for years that runners should work toward 180 strides per minute, this idea is more anecdotal than research-based. In this blog, we'll discuss the research surrounding cadence and why runners may want to focus on things other than cadence.

Where Did 180 Strides Per Minute Come From?

The year was 1984, and Los Angeles was hosting the Summer Olympics. Legendary coach Jack Daniels was sitting in the stands watching distance runners race 800m up to 10,000m on the Track. During these races, he made an interesting observation; the participants in this race all were running with at least 180 strides per minute.

He’s a very well known and well-published coach, so these findings spread and have stuck around ever since. Unfortunately these observations were then applied broadly to the running population.

Coach Jack Daniels’ findings imply a correlation not a causation

Some coaches will suggest that all runners should aim for 180 strides per minute. And I think this is the wrong way to look at the data. Jack Daniels’ findings showed a correlation --not a causation— between cadence and performance in distance running.

While Coach Daniels claims that he sees elite runners always run at 180+ strides per minute, this has not been what we’ve seen in subsequent analyses. You can do this yourself too! If you watch Olympian runners during their warm up or cool downs, they will often have a lower cadence, indicating that their cadence changes at different speeds. Here’s an example with marathoner Eliud Kipchoge. During his long runs he often runs with a cadence below 170. But if you watch him during a race like the London Marathon, his cadence will often be over 190 strides per minute. This is just one example, but you can find numerous examples of this phenomenon.

We’ve seen similar findings when looking at cadence in youth runners. This study found that youth runners varied their cadence at different speeds, and that runners with longer legs had a tendency to keep a lower cadence.

Changing Cadence Alters Running Biomechanics

When runners are told to increase their cadence during gait retraining sessions, we see changes in their biomechanics. These changes include:

- Decreased step length

- Decreased peak knee flexion angle (how much the knee bends)

- Decreased peak hip adduction (how much space is between the knees)

- Decreased peak knee extensor moment (amount of force exerted on the quads and patellar tendon)

- Foot strike ankle (less pronounced heel strike)

These biomechanical changes can be used to our advantage when treating a running related injury, but there doesn’t seem to be a protective effect that can be used to prevent running injuries.

The Dubious Relationship Between Cadence and Running Injuries

Lack of Data to Show Prevention of Running Injuries:

Vertical loading rate is often cited as a leading factor for running injuries. Vertical loading rate is the amount of force your body experiences from the ground as it pushes back up against you on every stride - specifically in the vertical direction.

There’s conflicting evidence on the relationship between cadence and vertical loading rate as described in this review. Some experiments show that changing cadence alters the vertical loading rate, while others do not. If you read any of the studies that examine cadence and biomechanics, you’ll see many statements like “shifting to a running cadence higher than one’s preferred MAY be helpful in reduction the risk of lower limb running injuries”. (1, 2)

The reason these papers say that increasing cadence MAY decrease injury risk, is because we don’t have any data that actually compares runners with a higher cadence vs. a lower cadence to look at differences in injury rates- we only can see changes in biomechanics.

It might seem easy to jump to the conclusion that changing biomechanics would prevent injuries, it’s not that simple. We see many interventions in physical therapy that are effective in treating injuries but don’t have the same effectiveness in preventing injuries on a population level. So we can’t say that increasing cadence reduces injury risk since there’s no data to support that claim.

Using Cadence as Treatment For Running Injuries:

While we can’t say that increasing cadence helps to prevent injuries, we do see good effects from cadence increases as a treatment for running injuries- particularly anterior knee pain.

There have been 3 studies that have shown a positive effect when using cadence as a treatment for patellofemoral pain. When using a gait retraining program to increase cadence 7.5% and 10%, the runners in these trials achieved a significant reduction in their knee pain that was retained 4 months after treatment began.

The main issue with these studies is they did not have a control group, so we can’t say how gait retraining compares to other treatments for patellofemoral pain. But the results are promising so far. We also haven’t seen this type of study for other running related injuries at the time this blog was published.

Conflicting Data on Cadence and Running Economy

Changing Cadence May Be Detrimental to Running Economy in the Short Term

As runners fatigue during a race, their cadence often slows. Coaches and runners will often try to increase cadence later in the race as a method of increasing efficiency. We have some data on this, and unfortunately it doesn’t totally support the idea that increasing cadence during a run increases running efficiency.

Back in 2007, researchers conducted an experiment looking at the relationship between cadence and O2 consumption at different cadences before and after a hard 1 hour run.

Early in the 1 hour run, the researchers measured oxygen uptake at the runners preferred cadence. They also measured O2 uptake at 4% and 8% above and below the runner’s preferred cadence. This same procedure was completed later in the run.

What they found was that runners used the least amount of oxygen at their preferred stride frequency. Later in the run, runners showed a decrease in their cadence. When runners were cued to increase their cadence later in the run, their efficiency went down. They used more oxygen while running at the same speed- which is not the effect you want late in a race.

This is just one example showing that increasing cadence does not improve running efficiency. There are several more studies that found similar results. What these studies find is that there is a U-Shaped curve when plotting out running economy and cadence- see image blow from Hunter and Smith 2007.

U-Shaped Curve

The data from Hunter and Smith 2007 shows that when cadence is lower or higher than the athlete’s preferred cadence, they use more oxygen.

But there’s a sweet spot in the middle where runners tend to self-select their cadence to be as efficient as possible.

There are more examples that support the U-shaped curve theory. A 2008 study measured cadence and oxygen consumption at different speeds. They also found that runners used the least O2 when running at their preferred cadence. Even at higher speeds, increasing cadence did not result in increased efficiency. You can read two more examples of studies that found similar results here and here.

Conflicting Long Term Data on Cadence and Performance

At the time that I’m writing this blog, there are only two studies that look at how a cadence retraining program effects running economy. One used a 6 week cadence training program, and the other was a 10 day cadence training program. These two studies vary dramatically in their procedures and their results.

6 week self-guided cadence program did not improve running economy

The 6 week study by Hafer et al in 2015 attempted to mimic a gait retraining program that a runner may undertake on their own.

The runners were given a log to record their compliance with the protocol. They were also given access to tools that help increase cadence, such as metronomes, music playlists that contain songs with tempos 10% higher than their preferred cadence, and free access to phones and computer that offer these features. These tools provided no real-time feedback to the runners to let them know how well they were increasing their cadence.

The runners were instructed to perform at least 50% of their training runs utilizing these tools to increase their cadence. After completing the 6 week protocol, the runners increased their cadence 2.5%, but no improvement in running economy was observed. Meaning that the increase in cadence did not make them more efficient.

There are a two major issues with this study: There were only 5 participants who completed the experimental protocol, and the compliance with the gait retraining program was only 61%. This study was performed in recreational runners. Poor compliance is a big issue that needs to be investigated, and we need this to be repeated with more participants.

A in-person treadmill gait retraining program increased running economy and cadence

The 10 day cadence retraining program from Quinn et al in 2019 showed different results. This study utilized a 10 day treadmill training program to increase cadence. A group of well-trained female runners participate in this study.

They came into the research lab every day for 10 days to complete each 15 minute cadence training session. They wore a switch on their foot which measured their cadence in real time and provided feedback on their performance. The runners were given cues to increase or decrease their cadence if they were not hitting the target of 180 strides/min. After leaving the lab, the runners were encouraged to try an maintain this cadence in their training sessions.

The runners who participated in this program increased their cadence by 5-8%, and improved their running economy 3-8%. This study had a high compliance rate of 96%. These results indicate that runners can increase their cadence and running economy with a structured cadence training program. Since this study differed in many ways from the 6 week program we don’t know for sure which variables were responsible for the positive effects. The key differences in this study were the length of time (10 days), the method of cadence training (in person treadmill training vs. self guided over-ground training), and presence of feedback (real-time feedback vs. no feedback), and compliance with the program (96% vs. 61%)

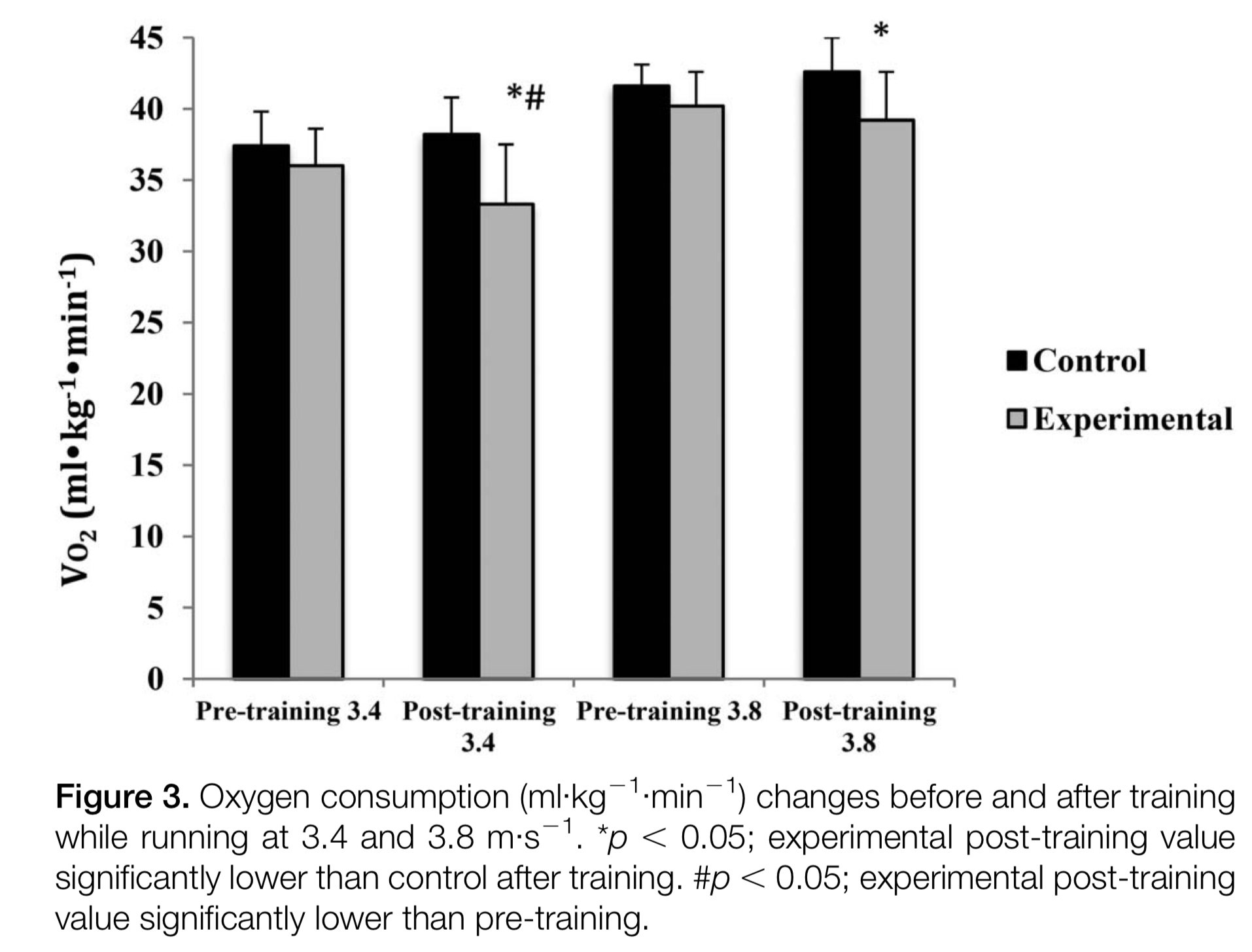

Improvements in Running Economy after 10 day cadence training

This figure from Quinn et al 2019 shows changes in oxygen consumption at 3.4 and 3.8 m/s. The control group showed no significant changes, while the experimental group improved their running economy at both 3.4 and 3.8 m/s.

Key takeaways from this data:

Self guided cadence training was not effective

The self guided program had a very small effect on cadence, and no effect on running economy. Poor compliance may be a key piece. The 6 week self-guided program had a much lower compliance rate than the in-person 10 day program. Without someone overseeing the program, it may be difficult to stick with it. Perhaps 6 weeks is too and runners start to lose interest as time goes on.

Or perhaps self-guided methods are ineffective alltogether. We won’t know until we see this this type of experiment performed again with better compliance or a different program duration.

In-person cadence training with real-time feedback DID improve running economy

The 10 day cadence retraining program looks to be effective at increasing cadence and running economy- though it may be difficult for runners to implement. This study involved in-person training sessions in a lab with fancy equipment. One result is a much higher compliance rate which could be a key piece. Perhaps runners need to work in-person with a coach to see real results.

The foot switch also provided instant feedback to the runner and they could adjust in real-time.Recent technology advances make this more possible, but runners still need to purchase some equipment and run on a treadmill with a screen to see their cadence. This could be done with a smartwatch as well, but it involves frequently checking your wrist, which changes the cadence reading while you check. You can review the data afterwards, but it’s not real-time feedback.

Regardless, these results show that it is possible to increase cadence and running economy. We just need to figure out which pieces of the program were most responsible for the benefits so that we can replicate it on a larger scale

Cadence May Be an Effect, Not a Cause of Increased Running Performance

Some runners will be heavily in favor of increasing their cadence, because they feel it worked for them. Perhaps they found some new method of increasing cadence and reducing injury, but the most common methods such as metronomes, playlists etc did not seem to be effective when studied. There are a few other reasons why runners may see benefits when focusing on their cadence which I’ll outline below:

1. If you are a new runner, you still might be optimizing your cadence

Data we have on cadence training typically invloves relatively experienced runners. When looking at running economy, we see that runners get more efficient over time. It can take some time to improve the neuromuscular control needed for your preferred cadence. In this case, I don’t think you need to stress about it. More running experience at a variety of speeds will help you to find your optimal cadence.

2. Your cadence may have increased as result of increased running performance or just training more

As discussed earlier, running cadence naturally increases as speed increases. You also self-optimize with more training. So if you start making progress with your runs and get faster, your training runs or races will likely have a higher cadence than before- especially on race day when you are running for speed.

3. It’s possible that your cadence increased as a result of improved running performance from the drills or training you performed.

We do know that sprint training and speed endurance training can improve running performance- thus increasing cadence.

We don’t really know how effective speed drills or jumping programs are for cadence in distance runners. These types of studies are typically done in sprinters, so we can’t apply that data to distance running. There is one study that looked at running biomechanics after doing a 4 week maximal jump program. They found no effect of the jump program, but I don’t think this study gives us any useful information. 4 weeks is not long enough to reap the benefits of a plyometric program, so we really don’t know if the jumping exercises have any effect on running biomechanics.

What SHOULD Runners Do

New runners should continue running, while incorporating different speeds

You can certainly experiment a bit with your cadence but you don’t need to. If you incorporate a variety of different speeds into your training— strides, intervals, tempo, or easy runs— it should sort itself out on its own. The more you run, the more your body will self-optimize and find the most efficient cadence naturally.

If you do try to alter your cadence, real-time feedback may be necessary to make meaningful changesIn the two studies described above, one resulted in changes to preferred cadence and increased running economy, while the other did not. The study that showed an effect utilized in-person training on a treadmill with instant feedback to track how well they were increasing their cadence.

Incorporate speed and plyometrics into your program

We’ve talked about why speed training is important, but plyometrics can be very beneficial as well. Plyometrics help to increase tendon stiffness, improve fast twitch muscle function, and improve neuromuscular coordination. All of these things can help boost running performance.

Try increasing cadence 5-10% as a treatment for anterior knee pain

The early studies show that increasing cadence can help to decrease anterior knee pain. I’ve seen this clinically for other injuries as well, but knee pain has been the only focus of research thus far.

Big Questions Remain

One major issue with the data on this topic is it all involves treadmill running. Treadmill running is different than outdoor running for a variety of reasons. We have no idea how any of these cadence training programs translate to running efficiency outdoors, because we don’t have the technology to measure oxygen consumption while runners move around outside.

We need more data to clarify why the 10 day cadence training program was more effective than the 6 week program. Was it the fact that the runners were well trained vs. recreational? In-person vs. self guided? Real time feedback vs. no feedback? Treadmill training vs. over ground training?

The short answer is we don’t know, but hopefully we do some more research to figure it out.

In the meantime, get out there and run, do some sprint training, some strengthening, and plyometrics!